|

We are taught that whether we did something unfavorable or inappropriate or bad, we shoould own up to it, that doing so is a sign of a responsible individual who recognizes his/her mistake and therefore can ensure not to repeat it in the future. Yet when it comes to the treatment, care, and training of our pets, why do we find ourselves more often than not blaming a 'lack of choice' for the bad decision, approach or outcome? Suzanne Clothier, a world renowned animal trainer, behavior specialist, and author shares her experience and outlook on the subject in her article titled "I Had To..." "I Had To..." |

||||||

| i_had_to_-_clothier.doc | |

| File Size: | 75 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

For one thing, Unless you can read a dog's mind, you have no knowledge or control over the associations they form during the application of aversives.

Secondly, the association you are forming is one of unpleasantness. This works great if you're talking about punishing for raiding the trash (trash can = bad) but when the object the association is being paired with is a human or animal, what kind of an association do you think your dog is forming?

As with the trash can example, it would be: Human & Dog = Bad. Sure he may stop barking or growling or lunging but those are mere "expressions" of the dog's internal state. Take away the expression, has the internal state changed?

If a dog who has previously reacted aggressively suddenly stops barking & lunging, does that mean he is no longer aggressive?

Would you then trust that dog to go out into public among people & other dogs?

My answer to that is: You can hate someone without lashing out at them; that is, you can hate someone without openly "expressing" your emotions about or toward him.

For example, growing up, most kids my age were told to act "nice" around their parents' friends' kids, regardless of whether we like one another or not. So when the parents were around, we'd all act like angels toward each other, but when they weren't...

When NOT under the control of the parents - just like when a dog is not wearing the e-collar - the kids' negative feelings would come out, because, being forced to hold back or suppress one's "expressions" of dislike toward another - which manifests itself in the form of bark &/or growl in dogs - it does not change the fact that that individual still dislikes the person (or dog) in question, same as before.

In my friend's case, she went from disliking to hating the other kid because she was continuously forced to go with her parents to their house & be in that girl's company. The continued exposure made her more & more unhappy & stressed, and she became very angry & hostile when she so much as heard the other girl's name being mentioned. Not to mention her resentment toward her parents who let her down by not taking her objections & unhappiness into account because "they" wanted to be there. So much for trusting them to provide a solution.

So let's go back to our dogs. You have a dog that is socially unskilled & therefore nervous. You, would good intentions, want him to go places with you thinking it'll be fun. But all he does is hide under the table & growl &/or snap any time a person tries to come near or pet him (remember my friend being forced to go to the kid's house she didn't like?). Instead of acknowledging that your dog is not happy being in that setting, in fact he's actually disturbed by it, you choose to get mad & jerk on his prong collar for growling & snapping. After all, you did him a favor by taking him out to a dog-friendly place.

BUT did you ask your dog if he wanted to be there? No. So, how is that fair to him? How do you justify your aggressive reaction to his unhappiness & inability to tolerate the pressure?

Secondly, the association you are forming is one of unpleasantness. This works great if you're talking about punishing for raiding the trash (trash can = bad) but when the object the association is being paired with is a human or animal, what kind of an association do you think your dog is forming?

As with the trash can example, it would be: Human & Dog = Bad. Sure he may stop barking or growling or lunging but those are mere "expressions" of the dog's internal state. Take away the expression, has the internal state changed?

If a dog who has previously reacted aggressively suddenly stops barking & lunging, does that mean he is no longer aggressive?

Would you then trust that dog to go out into public among people & other dogs?

My answer to that is: You can hate someone without lashing out at them; that is, you can hate someone without openly "expressing" your emotions about or toward him.

For example, growing up, most kids my age were told to act "nice" around their parents' friends' kids, regardless of whether we like one another or not. So when the parents were around, we'd all act like angels toward each other, but when they weren't...

When NOT under the control of the parents - just like when a dog is not wearing the e-collar - the kids' negative feelings would come out, because, being forced to hold back or suppress one's "expressions" of dislike toward another - which manifests itself in the form of bark &/or growl in dogs - it does not change the fact that that individual still dislikes the person (or dog) in question, same as before.

In my friend's case, she went from disliking to hating the other kid because she was continuously forced to go with her parents to their house & be in that girl's company. The continued exposure made her more & more unhappy & stressed, and she became very angry & hostile when she so much as heard the other girl's name being mentioned. Not to mention her resentment toward her parents who let her down by not taking her objections & unhappiness into account because "they" wanted to be there. So much for trusting them to provide a solution.

So let's go back to our dogs. You have a dog that is socially unskilled & therefore nervous. You, would good intentions, want him to go places with you thinking it'll be fun. But all he does is hide under the table & growl &/or snap any time a person tries to come near or pet him (remember my friend being forced to go to the kid's house she didn't like?). Instead of acknowledging that your dog is not happy being in that setting, in fact he's actually disturbed by it, you choose to get mad & jerk on his prong collar for growling & snapping. After all, you did him a favor by taking him out to a dog-friendly place.

BUT did you ask your dog if he wanted to be there? No. So, how is that fair to him? How do you justify your aggressive reaction to his unhappiness & inability to tolerate the pressure?

We humans are verbal creatures; so no wonder we rely on verbal commands to communicate with our dogs. Dogs however, are visual learners. While this distinction could put humans and dogs at odds with one another, fortunately science has found that the average dog has the language understanding of about a 2-year-old child. To put it in a human perspective, the average dog can learn 165 words. An intelligent dog can learn 250 words, and the very smartest dogs may be capable of much more. Such an example is Chaser, the border collie whose owner, John W. Pilley, Professor Emeritus Wofford College, taught him to identify more than 1,000 words. It is that outstanding ability of canines that enables our species to communicate so well with one another.

So what do researchers mean by “intelligence”? According to neuropsychologist Stanley Coren, Ph.D., author of Born to Bark, there are three major types of dog smarts: instinctive intelligence (what a dog is bred for), adaptive intelligence (what a dog can learn by itself), and working and obedience intelligence (what people can teach a dog to do). Other factors to consider is the level to which your dog is trainable, social, and able to understand human gestures and words.

Often we expect our dogs to either perform or stop performing behaviors that go against their instinctive intelligence. As a result, we have trouble teaching the behaviors ‘we’ want them to perform (i.e. teaching a terrier to fetch) and preventing the ones we don’t want them to perform (i.e. stopping a terrier from digging). Often this leads us to label our dogs as defiant or dumb. If, on the other hand, we were trying to teach a terrier to find a hidden toy in a sand pit, the rate of acquisition by the dog, the ease of teaching the task on hand, and the precision with which the dog performed the behavior would be so seamless that it would make the dog appear to be a genius and the handler a phenomenal trainer.

Researchers at the London School of Economics and Political Science and the University of Edinburgh devised an I.Q. test that they tested on sixty-eight working border collies. The dogs were tested on navigation (timing them on how long it took the dogs to get food that was behind different types of barriers); their ability to follow a human pointing gesture to an object; and whether they could tell the difference between quantities of food.

The results, as published in the journal Intelligence, stated that the dogs that did well on one test, performed better on the other tests as well, and those dogs that accomplished the tasks faster also showed more accuracy. Like with humans, dog intelligence comes in many forms, so it's hard to say whether one breed is really "smarter" than another, but border collies are considered one of the smartest breeds when it comes to training and obedience.

Is it true that dogs will weigh the value of doing something - Is it worth it? Sure! But more often than not the rate of performance, or lack thereof, is not due to the dog’s defiance or stupidity but rather his uncertainty about what’s being asked (either the dog hasn’t learned the command word or the behavior itself well enough to perform on command); how it’s being asked (handler is not using clear, known hand or verbal signals); where it’s being asked (the location or circumstance doesn’t match the environment in which the behavior was learned), and/or when it’s being asked (the dog has not been trained to perform in a state of high arousal or under pressure).

Hesitation on the behalf of the dog is an indication of uncertainty, just like when we humans hesitate to cut into traffic - we are unsure about the speed of the approaching car, the amount of time we have to jump into the gap, and whether the acceleration speed of our car will be appropriate to get us in and moving at the speed of traffic. And yet we drive on a daily basis and get plenty of real-life practice. Even so, the change in the pace of traffic on a given day, the difference in location and your current state of mind (anxious about the presentation you’re going to give at work) all affect our ability to process and perform what is a known task.

So the next time your dog takes a while to perform a behavior, don’t automatically assume he’s being defiant or question his intelligence, but rather consider the individual and environmental factors that may be involved. Keep in mind that with consistent, goal-oriented and appropriate training, your dog can learn to make decisions quicker and put forth a better performance displaying their true level of intelligence.

So what do researchers mean by “intelligence”? According to neuropsychologist Stanley Coren, Ph.D., author of Born to Bark, there are three major types of dog smarts: instinctive intelligence (what a dog is bred for), adaptive intelligence (what a dog can learn by itself), and working and obedience intelligence (what people can teach a dog to do). Other factors to consider is the level to which your dog is trainable, social, and able to understand human gestures and words.

Often we expect our dogs to either perform or stop performing behaviors that go against their instinctive intelligence. As a result, we have trouble teaching the behaviors ‘we’ want them to perform (i.e. teaching a terrier to fetch) and preventing the ones we don’t want them to perform (i.e. stopping a terrier from digging). Often this leads us to label our dogs as defiant or dumb. If, on the other hand, we were trying to teach a terrier to find a hidden toy in a sand pit, the rate of acquisition by the dog, the ease of teaching the task on hand, and the precision with which the dog performed the behavior would be so seamless that it would make the dog appear to be a genius and the handler a phenomenal trainer.

Researchers at the London School of Economics and Political Science and the University of Edinburgh devised an I.Q. test that they tested on sixty-eight working border collies. The dogs were tested on navigation (timing them on how long it took the dogs to get food that was behind different types of barriers); their ability to follow a human pointing gesture to an object; and whether they could tell the difference between quantities of food.

The results, as published in the journal Intelligence, stated that the dogs that did well on one test, performed better on the other tests as well, and those dogs that accomplished the tasks faster also showed more accuracy. Like with humans, dog intelligence comes in many forms, so it's hard to say whether one breed is really "smarter" than another, but border collies are considered one of the smartest breeds when it comes to training and obedience.

Is it true that dogs will weigh the value of doing something - Is it worth it? Sure! But more often than not the rate of performance, or lack thereof, is not due to the dog’s defiance or stupidity but rather his uncertainty about what’s being asked (either the dog hasn’t learned the command word or the behavior itself well enough to perform on command); how it’s being asked (handler is not using clear, known hand or verbal signals); where it’s being asked (the location or circumstance doesn’t match the environment in which the behavior was learned), and/or when it’s being asked (the dog has not been trained to perform in a state of high arousal or under pressure).

Hesitation on the behalf of the dog is an indication of uncertainty, just like when we humans hesitate to cut into traffic - we are unsure about the speed of the approaching car, the amount of time we have to jump into the gap, and whether the acceleration speed of our car will be appropriate to get us in and moving at the speed of traffic. And yet we drive on a daily basis and get plenty of real-life practice. Even so, the change in the pace of traffic on a given day, the difference in location and your current state of mind (anxious about the presentation you’re going to give at work) all affect our ability to process and perform what is a known task.

So the next time your dog takes a while to perform a behavior, don’t automatically assume he’s being defiant or question his intelligence, but rather consider the individual and environmental factors that may be involved. Keep in mind that with consistent, goal-oriented and appropriate training, your dog can learn to make decisions quicker and put forth a better performance displaying their true level of intelligence.

Bond with Your Dog for Maximum Training Results

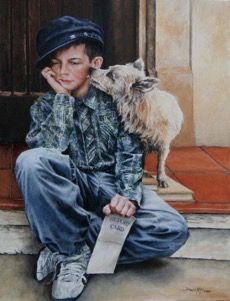

The bond between a dog owner and his canine can be a very strong one. Forming such a bond requires a genuine sense of care, affection, responsibility, and, above all, the demonstration of trust and respect.

This mutual trust and respect is also crucial to effective dog training. That is why “positive reinforcement” training is the preferred methodology of trainers and veterinary behaviorists of today. Positive reinforcement offers longer-lasting results compared to positive punishment, and it does so by maintaining the owner-dog bond. There is not an owner in this world that would not benefit from learning how to train his/her dog with the consistency and nurturing discipline of a positive approach.

Discipline is most effective when the dog owner maintains the bond and trust in instilling long-term habits. Just like us humans, dogs learn more effectively when they feel secure and comfortable. Consistent, positive bonding helps our dogs thrive and learn with maximum results, leading to a happy canine and a happy human.

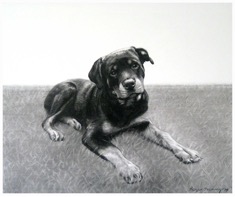

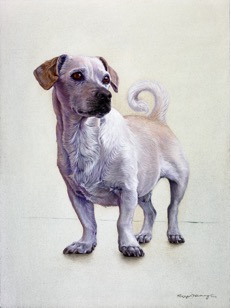

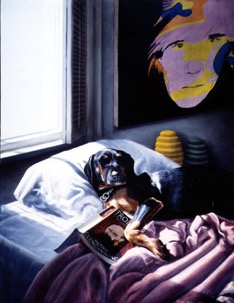

The animal-human bond can be seen in artworks throughout history. More recently, up for viewing are commissioned artworks in oil and pencil by artist Roger Henry, on exhibit at Dog and Horse Fine Art and Portraiture at 102 Church Street in downtown Charleston. The exhibit runs through November 1.

Henry is an international portrait artist living in Los Angeles, specializing in canines, equines, and humans. I found Henry’s work to be compelling, not just because of his subject matter, but also because of his attention to detail and the realism with which he portrays the emotions of his subjects at that instance. Details in Henry’s work reveal the personality traits of both the animal and owner and illustrate the mutual care and affection shared in the relationship. Henry says that he prefers to paint dogs the most, not surprisingly, because as the artist, he cannot help but form an affectionate bond with his canine subjects.

The art gallery features paintings and drawings of canines, felines, and equines by other notable artists, such as Beth Carlson, Lese Corrigan, and David McEwen, as well as spectacular bronze works. Visit Dog and Horse Fine Art and Portraiture and share in the joy of the artists bonding with their subjects.

This mutual trust and respect is also crucial to effective dog training. That is why “positive reinforcement” training is the preferred methodology of trainers and veterinary behaviorists of today. Positive reinforcement offers longer-lasting results compared to positive punishment, and it does so by maintaining the owner-dog bond. There is not an owner in this world that would not benefit from learning how to train his/her dog with the consistency and nurturing discipline of a positive approach.

Discipline is most effective when the dog owner maintains the bond and trust in instilling long-term habits. Just like us humans, dogs learn more effectively when they feel secure and comfortable. Consistent, positive bonding helps our dogs thrive and learn with maximum results, leading to a happy canine and a happy human.

The animal-human bond can be seen in artworks throughout history. More recently, up for viewing are commissioned artworks in oil and pencil by artist Roger Henry, on exhibit at Dog and Horse Fine Art and Portraiture at 102 Church Street in downtown Charleston. The exhibit runs through November 1.

Henry is an international portrait artist living in Los Angeles, specializing in canines, equines, and humans. I found Henry’s work to be compelling, not just because of his subject matter, but also because of his attention to detail and the realism with which he portrays the emotions of his subjects at that instance. Details in Henry’s work reveal the personality traits of both the animal and owner and illustrate the mutual care and affection shared in the relationship. Henry says that he prefers to paint dogs the most, not surprisingly, because as the artist, he cannot help but form an affectionate bond with his canine subjects.

The art gallery features paintings and drawings of canines, felines, and equines by other notable artists, such as Beth Carlson, Lese Corrigan, and David McEwen, as well as spectacular bronze works. Visit Dog and Horse Fine Art and Portraiture and share in the joy of the artists bonding with their subjects.